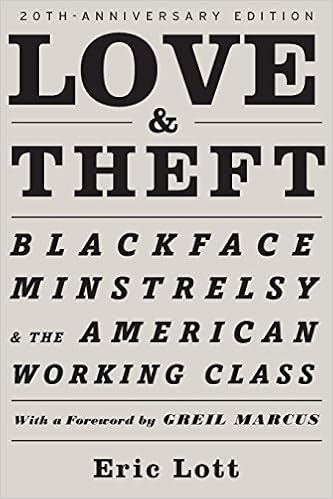

This is a really dense book that’s all about blackface performances in early America (1830-1860ish).

First thing is that a lot of people (even academics) avoid this topic so much. I took mad early American lit courses in undergrad, and blackface only came up one time–in a drama course my senior year. When I got to grad school and was in yet another early American class, the professor said something like how we’d be focusing on novels and poems because there wasn’t a lot of drama or anything. I was like, “uhh what about blackface??” I forget exactly what he said, but he kinda mixed me off and wanted to ignore them because, to him, they weren’t worth talking about because it was bad art and was therefore not worth studying. But, as this book shows, blackface performances weren’t just some underground shit. They were extremely popular and bled heavily into literature (re: Huck Finn, Moby Dick, etc.) and American culture.

The most overarching aspect of Love & Theft for me is (and was–when I first read this book in grad school) the hypervisibility of black people in America. So black people only make up a small population in the U.S., and yet they are pop culture. But, importantly, pop culture is merely a version of black culture–a whitewashed, highly-monitored, scaled back for the masses version. And the history of blackface helps explain how that came to be. American blackface in the 1800’s was white men dressing up as black characters for an all white audience. Their material (the songs, skits, lingo, mannerisms, etc.) mimicked black enslaved people. So some actors/writers would “study” black people in the south or elsewhere, then would come back to the north and put their own lil racist twist of their stuff. There would be two versions–the real song and the blackface version of that song. That is exactly how pop culture works in capitalism–the “reprocessing and containment” (105) of original (re)productions.

These performances also shaped how blackness is perceived. Lott is careful to point out that blackface performances didn’t just confirm racist stereotypes, but rather shaped them, anticipated them, and profited off them. Their costumes–the baggy clothes, the big nose, the big afro, the painted face–is literally where clowns come from. American blackface began with mostly songs and skits that were meant to be comical. What was so funny about a “black” person onstage doing some kinda jig? Well, Lott brings in Freud to show that part of the humor was about this triangular relationship between the actor, the audience, and the people being mad fun of. It was important that black people weren’t really there. It was important that black characters were presented as childlike–you know how kids say and do stuff that adults find funny because it’s just so innocent and like wow you don’t know anything do you! It was also important that not only were black people infantalized, but the audience was too (which was also part of the ~fun~). The big lips, big dick, big butt, etc. is basically a child’s view of sex.

Blackface’s style evolved over time however from songs and skits to also include sympathetic narratives (or song/narratives like “Oh Susanna,” which is about missing a dead woman). Most of the plot lines were about none other than… missing life on the plantation. So they would have a white guy onstage with black paint on his face saying damn I miss my massa in front of a group of white people. Sentementalizing that “nostalgia” ignited a trend in the U.S. where black stories in media rely on slave narratives, but it also spoke to the class fears that white workers had about slavery ending and black people coming to work alongside them. From there, (ironically) versions of the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin met the blackface stage. That’s where the Uncle Tom character was turned from a young, strong guy in the book to an old guy in pop culture.

Took me a while to read through this book, but it was worth it.

[…] in the that he had a class with Eric Lott, who wrote Love & Theft. Makes […]

LikeLike